by Clark Kauffman, Iowa Capital Dispatch

January 26, 2026

A federal judge has criticized what he calls the “indefensible” actions of federal immigration enforcement agents in Iowa, ruling they illegally detained a man in the Muscatine... more

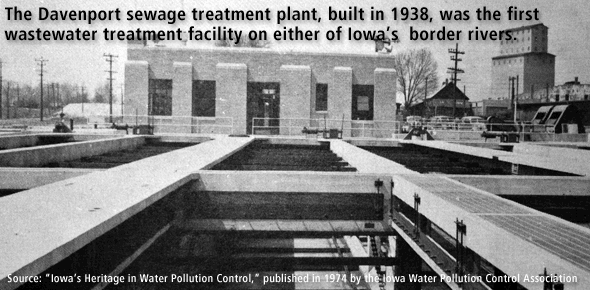

Iowa has a distinguished history for being in the forefront of wastewater treatment innovations, but the state's border communities were holdouts in building sewage treatment plants and allowed to dump untreated municipal and industrial wastes into the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers long after other cities along smaller streams were required to treat wastewater, according to a history of Iowa's water pollution control published in 1974 by the Iowa Water Pollution Control Association.

Writing in "Iowa's Heritage in Water Pollution Control," State Sanitary Engineer Paul Houser noted that the state's largest border cities along the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers were exempted from state stream pollution laws enacted in 1923 and 1949 "thanks to the lobbying power of the border cities and their industries.

"In fact, the exemption also included the lower 5,000 feet of any tributary, which was written specifically to protect the Sioux City meat packers dumping their untreated wastes into the Floyd River," Houser wrote.

Houser retired as State Sanitation Engineer in 1971 after serving 42 years with the Iowa State Department of Health. His recollections of the post-war years, 1946-1965, provides context to the continued use of the Mississippi River for dumping sanitary sewage overflows in Bettendorf and Davenport.

The two communities in late June and early July pumped millions of gallons of raw and partially treated sewage into the Mississippi after heavy rains and flood water seeped into sewer lines and overwhelmed the treatment capacity of the Davenport Wastewater Treatment Plant, jointly owned by the two communities along with Riverdale and Panorama Park.

"Looking back, it is interesting now to note that the attack on stream pollution in Iowa followed a sort of inverse or reverse pattern," Houser wrote. "First to face their responsibilities were the smaller towns and cities on the smaller inland streams, most of which had plants before 1925. Next were the larger cities on Iowa's three major interior streams, the Iowa, Cedar and Des Moines Rivers.

"Following stream surveys in the early 1930's, orders were issued to 17 cities on these three rivers, and all but Ottumwa built treatment plants before World War II," Houser recalled for the 1974 book. "But it was not until after the war that we were finally able to deal with municipal and industrial pollution of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers, involving some of Iowa's largest 'first-class' cities, as they were designated at that time."

The city of Davenport did build a primary sewage treatment plant before World War II in 1938 in conjunction with construction of an interceptor sewer line along the Davenport riverfront by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. It was the first treatment plant built on either of Iowa's border rivers.

The corps of engineers built the interceptor for Davenport, Houser recounted, to carry raw sewage to a point below Lock & Dam 15, "thus removing it from the upstream pool which served the city both as a water supply and a boating and recreational area."

The corps of engineers built the interceptor for Davenport, Houser recounted, to carry raw sewage to a point below Lock & Dam 15, "thus removing it from the upstream pool which served the city both as a water supply and a boating and recreational area."

Ironically, it is the very same Corps of Engineers interceptor that is suspected today of allowing large amounts of flood water and storm water runoff to infiltrate, helping to exacerbate capacity issues at the treatment plant along Concord Street, Davenport.

Crews are exploring the Corps interceptor line this summer to determine how to reduce infiltration and remove any sedimentation in the large pipe. The work is part of a 20-year, $160-million upgrade of the Davenport-Bettendorf sewer system which is required under an administrative consent order the cities signed with the Iowa Department of Natural Resources in 2012.

by Clark Kauffman, Iowa Capital Dispatch

January 26, 2026

A federal judge has criticized what he calls the “indefensible” actions of federal immigration enforcement agents in Iowa, ruling they illegally detained a man in the Muscatine... more

by Robin Opsahl, Iowa Capital Dispatch

January 22, 2026

Iowa House Democrats released a proposal Thursday aimed at improving the quality of Iowa’s drinking water and waterways through increased monitoring and more incentives for farmers... more

by Cami Koons, Iowa Capital Dispatch

January 15, 2026

Chris Jones, an author, researcher and Iowa water quality advocate, launched his campaign for Iowa secretary of agriculture Thursday outside of Des Moines Water Works.

Jones’... more

by Clark Kauffman, Iowa Capital Dispatch

January 15, 2026

A federal judge has ordered the Muscatine County Jail to release an ICE detainee who had been incarcerated for almost a year after a judge ruled in his favor on an asylum request... more

Powered by Drupal | Skifi theme by Worthapost | Customized by GAH, Inc.