by Clark Kauffman, Iowa Capital Dispatch

January 26, 2026

A federal judge has criticized what he calls the “indefensible” actions of federal immigration enforcement agents in Iowa, ruling they illegally detained a man in the Muscatine... more

If I hold to be true that absurdity determines my relationship with life, if I become thoroughly imbued with that sentiment that seizes me in the face of the world’s scenes, with that lucidity imposed on me by the pursuit of science, I must sacrifice everything to these certainties and I must see them squarely to be able to maintain them. Above all, I must adapt my behavior to them and pursue them in all their consequences. I am speaking here of decency. But I want to know beforehand if thought can live in those deserts. –

In geology, ‘drift’ refers to all the debris transported and deposited by glaciers or their meltwater, and this glacial garbage in Iowa can be as much as 500 feet thick. Glaciers spread it across the landscape like peanut butter on an English muffin, masking surface roughness and leaving much of the landscape approximately level.

In this part of the North America, little was left untouched by glaciers save a roughly oval piece of plain muffin we call ‘The Driftless’ that covers 20-70 miles east of the Mississippi River from Durand, Wisconsin down to just south of Galena, Illinois. I’m sorry to tell my fellow Iowans (and Minnesotans) that we’re really just Driftless wannabes; our part of the ‘Driftless’ isn’t without drift, it just looks like it. But that’s a story for another day and for convenience I’m just letting that go for now.

In this part of the North America, little was left untouched by glaciers save a roughly oval piece of plain muffin we call ‘The Driftless’ that covers 20-70 miles east of the Mississippi River from Durand, Wisconsin down to just south of Galena, Illinois. I’m sorry to tell my fellow Iowans (and Minnesotans) that we’re really just Driftless wannabes; our part of the ‘Driftless’ isn’t without drift, it just looks like it. But that’s a story for another day and for convenience I’m just letting that go for now.

Beautiful map of the Driftless (and Driftless-like) area prepared by Phil Kerr of the Iowa Geological Survey

As you probably know, I’m a big fan of the ag communication shops and can hardly imagine what Iowa would be like without them. Creativity flies out of these idea Edens like hog shit out of a honey wagon.

I’ve been hearing a lot from them these days about the increased number of trout streams in Iowa’s part of the Driftless, and how this is yet one more reason why we should fall to our knees and cry hosanna to Saint Harold of Garnavillo and all the rest of the sainted sodbusters that supposedly make Iowa the Environmental Elysian of the ag world.

On a whim, I decided to explore ag’s trouty claims with some of the level-headed fisheries biologists at Iowa DNR. I know you’re thinking Jones, if Iowa Farm Bureau says something, it's rock-solid dude, move on to what’s important in an institute of higher learning, like writing journal papers that six people will read, or making your pet words trendy.

As luck would have it, DNR scientists did indeed have something to say about this subject, and lo and behold it had already been summed up in an excellent 2020 document titled “A Plan for Iowa Trout Management,” which they eagerly sent to me. Gracious readers, allow me to provide you some takeaways from the document.

First, we can’t be certain that trout are native to Iowa, although it seems very likely that Brook Trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) are. Fisheries biologists know that they are native to Driftless Wisconsin and Minnesota, so it’s not a stretch to imagine they made it into Iowa waters via the Mississippi River.

Driftless area streams fed by groundwater from limestone formations are tempered in both the summer and winter by the clear, cool water that trout require. There are a total of only nine Iowa streams thought to hold native brook trout, most tributaries of the Upper Iowa River in Winneshiek and Allamakee Counties.

The state has been trying to manage for Brook and other trout species since 1875, when Brookies were stocked in Jones County. DNR got serious about trout management in 1983 when the first trout program was published.

The plan “highlighted the need for put-and-take stocking (stocking catchable fish explicitly for sport fishing in streams where natural reproduction is low or non-existent) and the importance of acquiring additional trout stream access.” DNR created a priority list of streams that now have lengths held in public trust by DNR and other conservation groups.

This is important to recognize because there are now 120 miles of trout streams that flow through public land in Iowa and 16 more stream miles with permanent easements. Consider this strongly alongside agriculture’s attempts to limit public land for Iowa citizens, including yet another bill currently making its way through the Iowa legislature. An Iowa Farm Bureau Federation representative recently said that the group supports the new legislation “specifically because it would limit new public land acquisitions,” and that “The Farm Bureau has been advocating for years to keep more land available for farmers to buy (1).”

Many of the ‘put and take’ fish were Rainbow and Brown Trout. In North America, Rainbows are native only to watersheds west of the continental divide but are an exotic species introduced to many parts of the U.S. and Canada because they are easy to feed and raise in a hatchery. Brown Trout are native to Europe and were first stocked in Iowa streams in the 1940s. Both Rainbows and Browns are more tolerant to high temperature and low oxygen than are Brookies, and there is some evidence that European Brown Trout have adapted to water pollution (2). Rainbows and Browns grow much larger than Brookies.

There were no stockings of Brook Trout from 1956 to 1977. From 1977-79, Brookies were unsuccessfully stocked in North Cedar Creek and South Fork of Big Mill, and the species was not stocked again until 1993. The ’77-79 fish were obtained from a Wisconsin hatchery and were a New Hampshire strain. In 1995, a comparative genetic analysis of Brook Trout was conducted by Iowa DNR scientists.

The researchers determined that Brookies from Iowa’s South Pine Creek had low genetic diversity and thus were considered a ‘relic’ or holdover population uniquely adapted to the area. At the time DNR focused on preserving the gene pool, and not depleting the South Pine population by moving them elsewhere.

A year later, however, DNR began stocking South Pine Brookies into other NE Iowa streams to prevent a possible catastrophic loss of the genes from human or natural upsets on South Pine. By the early 2000s, South Pine Brook Trout populations had declined and egg harvest was suspected as the driver, so DNR consequently stocked Wisconsin Ash Creek strain Brookies in Iowa Streams in 2006, 2009 and 2010.

Since then, the South Pine strain has dominated stocking (30 streams vs 3 for the Ash Creek strain) and not surprisingly their Iowa genes have proven to be well-adapted to Iowa streams and they are successfully spawning in many of them. Natural reproduction is critical for effective trout management and anglers tend to prefer the ‘wild’ character of these fish, versus those raised fat, lazy and dumb in a hatchery. Long and short, the discovery and characterization of the South Pine strain of Brook Trout by Iowa DNR fishery biologists was key in the expansion of sustaining Brook Trout populations in NE Iowa.

Similarly, the strain of Brown Trout in Allamakee County’s French Creek was discovered to be well adapted to Iowa conditions long after the species was first stocked in Iowa. Since Browns and Brookies both spawn in the fall they’re not likely to thrive in the presence of the other, and a native Brookie (the Goldilocks of the trout world) is likely to lose out to the burly Brown in small Driftless streams.

Thus, the French Creek strain of Brown Trout is stocked where Brook Trout stockings have failed, and Brown trout are naturally reproducing in many NE Iowa streams. There are now more than 80 streams in Iowa where trout successfully spawn without human intervention. This indeed is a triumph for the fisheries biologists that have worked for Iowa DNR over the past 40 years.

Largely left out of the story thus far, Rainbow Trout make up almost all the 340,000 catchable trout currently stocked into Iowa streams each year. These are still stocked as a put-and-take species in streams and are also stocked in urban ponds to provide ice fishing opportunities for trout. Stocking of catchable sized Brook and Brown trout were discontinued in 2020 and 2006, respectively, as the fisheries scientists have been able to establish successfully spawning populations of those species.

Another big component of this story is climate change, and not the way you might think. Because Iowa has gotten wetter (a lot wetter in fact), water is maintained in these spring fed trout streams such that severely low flows rarely threaten trout survival. This allows trout to carryover year after year after year as long as they can successfully spawn. There’s a school of thought out there that the trout range in Wisconsin’s Driftless is more expansive now compared to before European settlement because of this reason.

So, you may have noticed that any mention of Saint Harold and His Sodbusters is thus far absent from this story.

DNR stated in 1987 that “some natural reproduction of Brown Trout occurs (in NE Iowa), but it is generally very limited by poor water quality caused mainly by extensive soil erosion.”

It was still rare to find naturally reproducing trout in stream surveys conducted in the mid-1990s, a decade after farmers were required to adopt soil conservation practices aligned with Conservation Compliance in the 1985 Farm Bill (3). This is a key point because improvements in soil erosion plateaued at that time (mid-‘90s), implying that the subsequent identification of adapted strains was key.

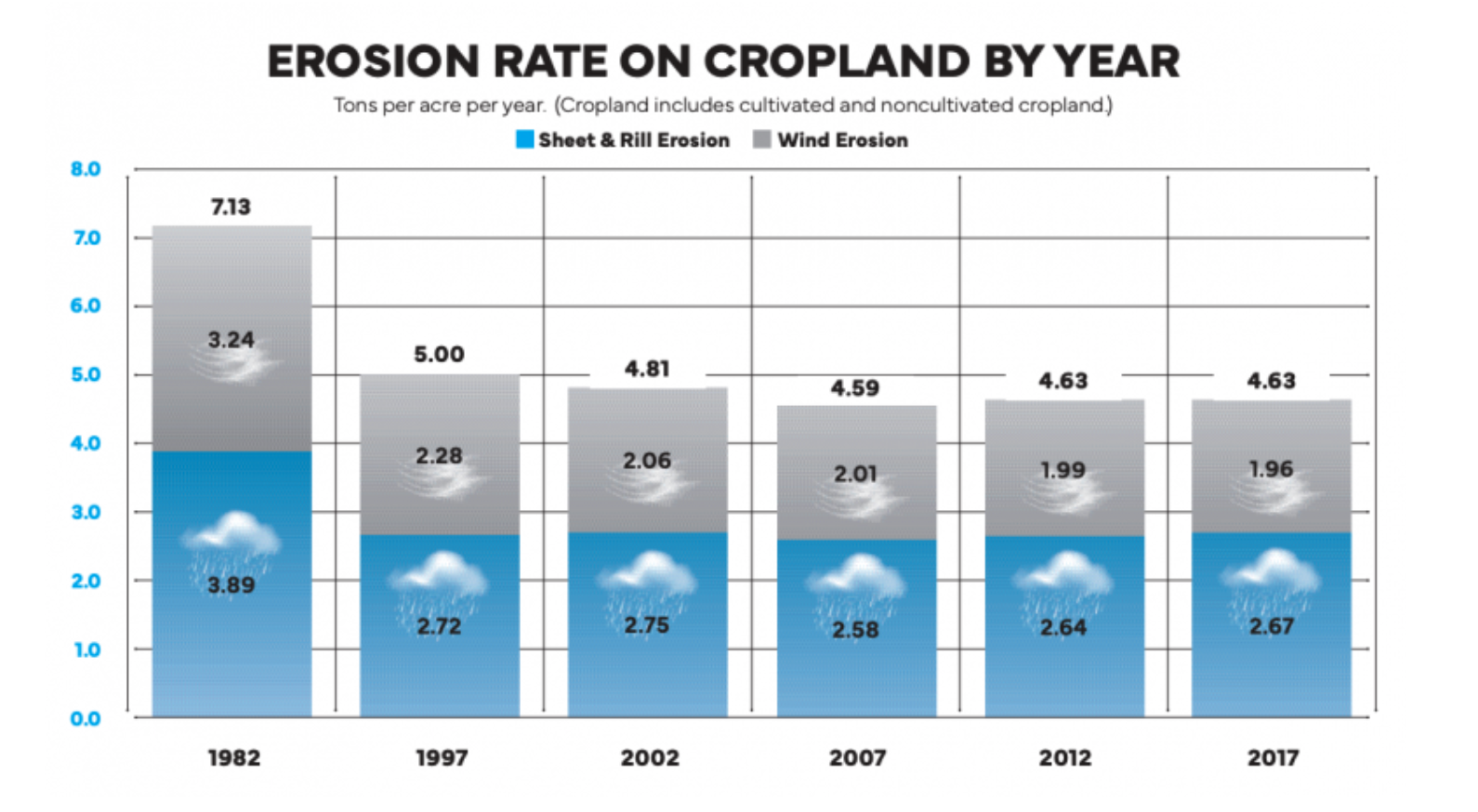

Graph taken from Successful Farming (citation 4), based on The National Resources Inventory (NRI) program from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service. Iowa Farm Bureau claims a 47 percent improvement in soil erosion since 1982, but most of that improvement occurred prior to 1997.

DNR does state that trout restorations have benefitted from “improved stream habitat resulting from more coldwater input (lower water temperatures), decreased presence of fine (silt) sediment in the bed load and as suspended material, and instream habitat improvement practices; (and) changed land-use practices that include less new expansion of agriculture and forestry into previously undisturbed areas, as well as reduced intensive grazing and reduced tillage that has improved infiltration of rainfall.”

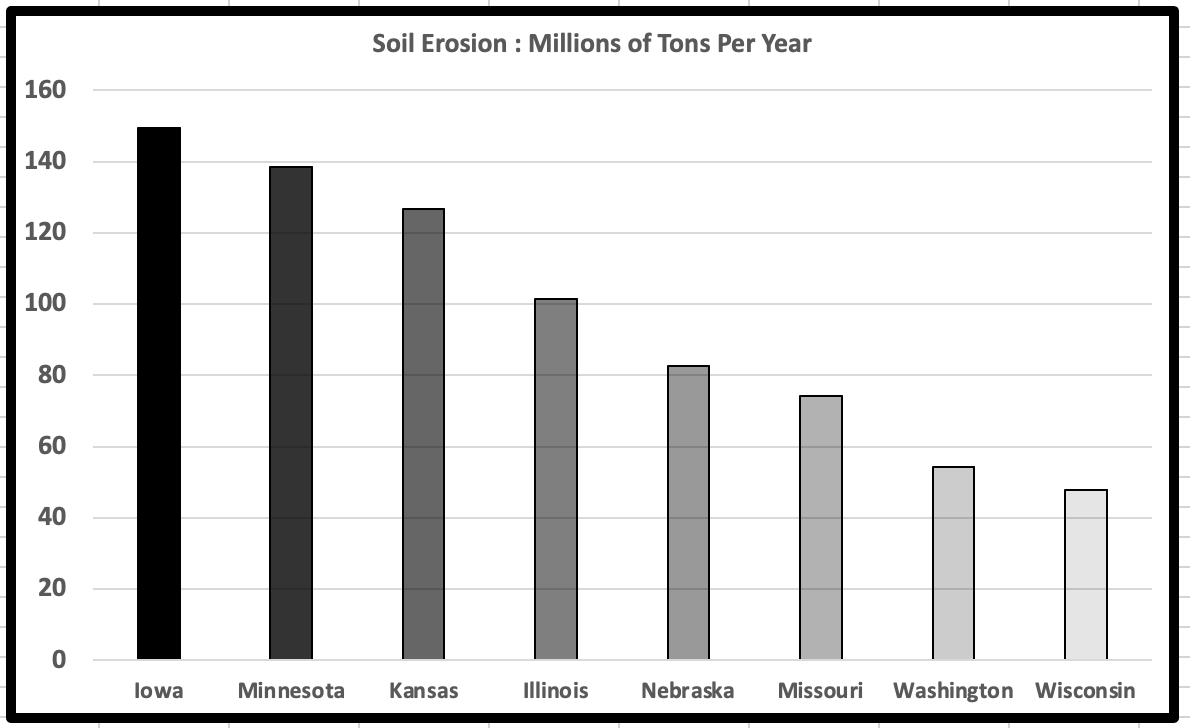

Soil erosion is still terrible in NE Iowa and the region is largely responsible for the state’s dubious distinction of leading the country in departed dirt (4). I wish to emphasize that erosion did decrease after LAWS forced farmers to adopt soil conservation measures aligned with Conservation Compliance in the 1985 Farm Bill (3), but little progress has been made since 1997.

Top soil erosion states. Data source: National Resources Inventory, USDA.

Now let me make clear that Driftless farmers and landowners that work with conservation organizations to enhance trout habitat and improve the general condition of streams deserve our thanks and admiration. But if there’s anything beyond fisheries science that should be touted as crucial to Iowa’s trout success story, it’s the idea of what’s possible when cropped land is limited to less than half the watershed area, which is the case in much of Iowa’s Driftless.

About 70 percent of Iowa’s land is cropped to corn and soybean, and in some watersheds that figure approaches 90 percent.

Here are the percentages in some of NE Iowa’s trout-holding watersheds: Upper Iowa River, 47 percent; Yellow River, 50 percent, Turkey River, 57 percent; Bloody Run Creek, 48 percent; Waterloo Creek, 19 percent; Catfish Creek, 48 percent; French Creek, 24 percent; South Pine Creek, 23 percent; Trout Run, 52 percent; Bear Creek, 30 percent.

Let me (almost) finish this by saying that establishment agriculture claiming credit for improved trout fishing is repulsive, and in my estimation an insult to the fisheries scientists that have worked to make this happen these past 40 years.

Can you find improvements in land management since 1980? Of course. But take a drive through the Driftless on any day of the year and you will see horrible land management decisions almost anywhere you look.

I’ve witnessed the ag propaganda machine from within and without for quite a while now and have often wondered how their absurdities could matter.

But matter they do as we hear politicians from both parties and farmers across the spectrum barf them out regularly.

I’ve also come to believe that this stuff has become a drug to many in agriculture, used and abused to self-medicate and relieve the guilt some must have for turning much of the state into an environmental wasteland.

And if you’re still thinking the industry might give two turds about Iowa trout fishing, ask yourself who in the industry has said even one word in opposition of the now operating 11,600 head cattle operation near the headwaters of Bloody Run Creek, one of the self-sustaining trout streams and a stream with the designation of Outstanding Iowa Water.

In Greek mythology Sisyphus was a guy that led a lucky life, something that rankled the god of the underworld who then subsequently punished him by alternately forcing him to roll a BFR up a hill and then watch it roll back down. For eternity. Now I know some of you must think I’m about to compare myself to Sisyphus. If so, I’m happy to disappoint you. Besides, Hades knows he could never force me to do any such thing.

I bring up Sisyphus because many have examined the myth to gain insights on the absurdity of life, most famously Albert Camus (quote at the beginning) who wrote The Myth of Sisyphus (1940).

The essay (I’d recommend the Cliff Notes version of anything Camus unless you think the remainder of your life will be lengthy) introduced me to the idea that there are “truths but no truth” when absurdity reigns.

It occurred to me that this is an accurate characterization of the current situation in our country and our state and especially the relationship between agriculture and our water quality.

Industry players from top to bottom love cherry-picking but wouldn’t know a cherry pie if it hit them in the face.

They love the little truths, but there is no truth for them beyond what they want it to be.

You see it in their rhetoric: feeding the world, the first environmentalists, we don’t want to lose our soil and nutrients, thank us for the trout, etc., etc., etc.

Certainly, agriculture is not alone in this and we see it everywhere we look in society these days.

The COVID pandemic was the mother lode of ‘truths but no truth’, and the idea that there is no truth has infected our institutions and politics as surely as COVID infected our bodies. This is clearly deliberate and is what happens when facts conflict with an unchangeable worldview and determined self interest.

Many besides Camus have written about this and of course the most well-known of these was Orwell.

The propaganda of both the communists on the left and the Nazis on the right scared him, in his own words, more than the bombs on London. He observed that Nazi theory “indeed specifically denies that such a thing as ‘the truth’ exists (5).” To think that politicians are only responsible for this perversion is wrong, as Orwell saw: “One feature of the Nazi conquest of France was the astonishing defections among the intelligentsia, including some of the left-wing political intelligentsia (5).”

As we move forward trying to improve the environmental condition here in Iowa, we have no choice but to work with agriculture, if not for nothing but the simple reason that they own or control almost all the land.

They also are the state’s strongest force in the legislature; less than 3 percent of our population is farmers but they comprise over 20 percent of the legislature, at least by my count.

That being said, both their actions and their words call to question whether the industry is a good faith partner when it comes to water and the environment. In my estimation, they are not.

In a functioning system, the obvious remedy to this is laws. But as we see, year after year, laws seem as likely as industry honesty.

Are we doomed to a Sisyphusian fate? Maybe. But as Camus says, "There is no fate that cannot be surmounted by scorn."

+++++++++++++

(1) Strong, J. Stalled public lands bill moves forward in Iowa House. Iowa Capital Dispatch, March 20, 2023.

(2 )Science Daily, July 24, 2013. Extraordinary trout has tolerance to heavily polluted water.

(3) Padgitt, S. and Lasley, P., 1993. Implementing conservation compliance: Perspectives from Iowa farmers. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 48(5), pp.394-400.

(4) Schilling, M. The State of Erosion on U.S. Farms. Successful Farming, February 2, 2022.

(5) Orwell, G. Looking Back on the Spanish War. New Road, London, U.K. 1943.

by Clark Kauffman, Iowa Capital Dispatch

January 26, 2026

A federal judge has criticized what he calls the “indefensible” actions of federal immigration enforcement agents in Iowa, ruling they illegally detained a man in the Muscatine... more

by Robin Opsahl, Iowa Capital Dispatch

January 22, 2026

Iowa House Democrats released a proposal Thursday aimed at improving the quality of Iowa’s drinking water and waterways through increased monitoring and more incentives for farmers... more

by Cami Koons, Iowa Capital Dispatch

January 15, 2026

Chris Jones, an author, researcher and Iowa water quality advocate, launched his campaign for Iowa secretary of agriculture Thursday outside of Des Moines Water Works.

Jones’... more

by Clark Kauffman, Iowa Capital Dispatch

January 15, 2026

A federal judge has ordered the Muscatine County Jail to release an ICE detainee who had been incarcerated for almost a year after a judge ruled in his favor on an asylum request... more

Powered by Drupal | Skifi theme by Worthapost | Customized by GAH, Inc.